Our earliest detailed account of the life of Jesus of Nazareth is found in the Gospel of Mark. The earliest communities of Jesus followers were committed to the idea of the imminent kingdom of God and the return of Jesus within their own lifetimes (I’ve written elsewhere about this here and here). The Gospel of Mark arrives after the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem and after the passing of the first generation of Jesus followers. By that time, the kingdom had not arrived and Jesus had not returned. Texts like the Gospel of Mark, which captured the life and teachings of Jesus, may have become necessary for growing and evolving communities committed to this enigmatic figure. But what do we know about this first gospel and how might we best categorize it? In this post, we’ll touch on questions of dating, authorship, and genre categorization in order to establish a framework for understanding and interpreting this pivotal text.

Dating and Authorship

Like all of the canonical Gospels, Mark was written in Greek. This tells us that the author likely had a decent level of literacy,1 placing them within a small population of the ancient world with the capability to read and write. Traditionally, this gospel is said to have been written by an associate of Jesus’ disciple Peter. In the early 2nd century, a bishop named Papias said that someone named Mark interpreted and wrote down the recollections of Peter. Unfortunately, we have no way of knowing if the text Papias is referring to is what we now know as the Gospel of Mark or if it was some other text that has been lost because Papias does not quote anything from this text he is referring to. It is also worth mentioning that we do not have surviving texts directly from Papias himself. Instead, his writings are preserved in the writings of the 4th century Church Historian Eusebius who, to be frank, thinks that Papias is an idiot,2 perhaps not someone he considered a trustworthy source.

It is not until the end of the 2nd century that we have someone quoting a text attributed to someone named Mark,3 and not until near the end of the 4th century that we have our first complete copy of the Gospel of Mark. In other words, the first complete copy that we have is over 300 years removed from the events that it reports. This complete copy is found in the Codex Sinaiticus (you can access a digital version of this codex here), a Greek volume containing the oldest complete copies of the New Testament, including texts like the Shepherd of Hermas and the Epistle of Barnabas which were long considered to be part of the Christian canon in various parts of the ancient world. In this codex, what we call the Gospel of Mark begins with the phrase ΚΑΤΑ ΜΑΡΚΟΝ, meaning “according to Mark”. So, we can at least be confident that by the late 4th century, this text that we are familiar with was attributed to someone named Mark.4

Hopefully this all starts to paint an opaque image of the authorship of this text. There is a long line of scattered references to a gospel written by someone named Mark, but it is not until between the late 2nd and late 4th centuries that we can begin to see a correlation between what we know as the Gospel of Mark and what our ancient sources provide. The Gospel of Mark itself, furthermore, does not claim to be written by anyone in particular. It is anonymous and is only attributed to someone named Mark much later in order to validate it as an important text written by someone who knew a disciple of Jesus.

-The beginning of the Gospel of Mark as found in the Codex Sinaiticus, a 4th century volume containing the oldest complete copy of the Gospel of Mark. Source: https://www.codexsinaiticus.org/en/manuscript.aspx?__VIEWSTATEGENERATOR=01FB804F&book=34&lid=en&side=r&zoomSlider=0.

It is uncertain where the Gospel of Mark was written, although prominent theories place it within Rome or Syria. Most scholars believe it was written sometime after the year 70 CE in the aftermath of the First Jewish Revolt and destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem.5 The dating of any ancient text is very difficult and involves several different spheres of study such as thematic and narrative examinations, comparison to known historical events, language studies, and papyrology (the study of ancient papyri, which most New Testament texts were written on).

Most critical scholars view Jesus’ predictions of the Temple destruction as evidence that Mark was written after 70 CE when the Temple was destroyed. The Markan Jesus is also the most apocalyptically-minded, so to speak, announcing the imminent arrival of the kingdom of God and end of the present age. Such portrayals of Jesus may very well be historical, but the fact that the Markan text preserves heavy apocalyptic themes is often taken as evidence that it was produced near enough to the time of apocalyptically-minded figures like John the Baptizer, Jesus, and Paul of Tarsus that expectations for the end of the age and Jesus’ triumphant return were still prominent. All of this allows us to determine with a fair degree of probability that the Gospel of Mark was written no earlier than 70 CE and likely within one generation after Jesus’ death.

Genre Categorization

Debates over the best way to categorize Mark have been present for centuries with varying genre labels such as ancient biography,6 performance script,7 or a unique genre all its own.8 While there is still debate about the best way to categorize the genre of Mark, what most critical scholars now agree upon is that it is not portraying pure history, if such a thing could be portrayed at all, but is instead a piece of literature whose author takes creative measures to make statements about the person of Jesus. Robyn Faith Walsh calls this author a creative writer, one who dynamically engages with their subject matter.9 Many of Jesus’ interactions in Mark, for example, center around the Temple and its destruction, a nod to the post-70 CE environment the author was likely writing in where the Temple, its customs, and its once prominent figures have been relegated to a bygone age. Motifs of Temple destruction (Mark 11:15-18, 12:1-2, and 13:1-2), calamity (Mark 13:7-8), and Jesus’ teachings which subverted Temple-centered life (Mark 2:27-28 and 7:1-3) are just a few examples which suggest that Mark may be reflecting upon literal events and laying theological beliefs about Jesus over them. As such, the Markan text may be categorized, not as history or fiction, but as history and fiction, refracting real events through the prism of theology and giving us what John Dominic Crossan calls “prophecy historicized”.10

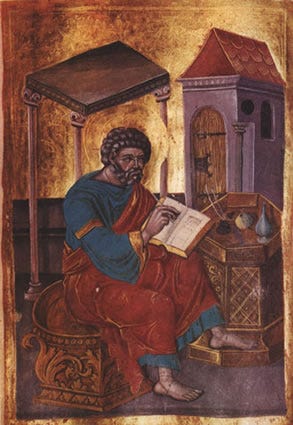

-Mark the Evangelist, 16th century. Source: Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=117526.

The Gospel of Mark as Ancient Biography

Of the various genre labels that have been suggested, I believe that the Gospel of Mark most closely aligns with ancient biographies. It does have a few notable differences from most ancient biographies, such as the lack of a birth story and a perplexing death scene, but the way in which Jesus is elevated as a moral exemplar is undeniable. The temptation to label Mark as a text with an entirely unique genre (a past and occasionally present perspective) seems more a biproduct of Christian exceptionalism rather than an evidence-based conclusion. This text was not produced in a vacuum but was the result of an author playing with tried and true literary methods. What made Mark stand apart from other types of ancient biographies was its protagonist.

Rather than give factual recollections of prominent figures, ancient biographies in the Greco-Roman world were meant to uplift the protagonists of these texts as moral exemplars. This was often done through characterization, a strategy through which attributes are imbued within characters in a text. Characterization was a common tool of ancient biographers, who “blended fact with a degree of creativity, from fictive accounts of birth and childhood to freely-composed speeches.”11 Biographies of prominent ancient figures were common, capturing the moral qualities of philosophers, military leaders, and political entities. Secondary characters in ancient biographies were often portrayed as certain types of individuals, ones who were not important in and of themselves, but for the effect they had on the broader plot or protagonist of the text.12 The audiences of ancient biographies were intended to “extract the moral qualities” of the protagonist and seek to apply those qualities to their own lives.13

Take, for example, the friends of the paralytic man in Mark 2, Jairus in Mark 5, or the Syrophoenician woman in Mark 7, all of whom are characterized as faithful followers of Jesus. By contrast, figures like the wealthy man with many possessions in Mark 10 or Judas Iscariot are imbued with traits which should not be emulated by Mark’s audience. Most of all, Jesus is characterized by his words, actions, and exchanges with the other characters in the text and is consistently presented as a moral exemplar, often in contrast to various foils like Judas, Barabbas, or his own disciples. Jesus is portrayed as someone who demonstrates a way of living rather than a way of believing, per se, and is characterized much more by his actions than his words (this tends to change as later gospels are written).

Understanding the Gospel of Mark as a type of ancient biography emphasizes the need to read it within its literary context and calls into question the intended historicity of the text. The author was not necessarily trying to portray pure history, but was instead trying to say something about the person of Jesus.

Conclusion

How might reading the Gospel of Mark as a type of ancient biography change the way we read this text? For me, it places it within a literary and cultural context that helps me better understand some of the narrative aspects of the Markan story and causes me to always remember that the author is trying to make exemplary statements about Jesus, often at the expense of other characters or groups within the text. The post-70 CE world that the author of Mark was writing in was filled with competing stories about the future of Judaism and the burgeoning Christian religion, and our earliest gospel helped set the direction for future stories about the person of Jesus as a figure to be followed and emulated.

Reading Suggestions:

-Roman Lives by Plutarch (this is a selection of biographies by the Greco-Roman biographer Plutarch, translated by Robin Waterfield)

-The First Biography of Jesus: Genre and Meaning in Mark’s Gospel by Helen K. Bond

-The Origins of Early Christian Literature: Contextualizing the New Testament Within Greco-Roman Literary Culture by Robyn Faith Walsh

It is possible that the author, the one composing the narrative of the text, was different from the one actually writing the text down. It was very common in the ancient world for authors to dictate letters or stories to other people, often enslaved individuals, who would be the ones writing the words. It was not guaranteed that someone dictating a letter or story was able to write as well, since these two skills did not always go hand-in-hand. We know that Paul of Tarsus dictated his letters (see Romans 16), and it is very possible that the authors of the Gospels did as well.

Eusebius. The Church History. 3.39. Translated by Paul L. Maier. Grand Rapids: Kregel Publications. 1999.

The Church Bishop Irenaeus quotes Mark in his work Against Heresies around the year 180 CE.

This is not to say that the Gospel of Mark found in this codex is a word for word match with what we have today. If you are reading a responsibly translated Bible, you can see the different variations of the text which are found throughout the manuscript tradition, including, but not limited to, the Gospel of Mark omitting the words “Son of God” from the first verse and ending the Gospel at 16:8, with the women fleeing Jesus’ empty tomb in silent fear.

Many scholars argue for a post-70 CE date for the Gospel of Mark, including but not limited to, Bart D. Ehrman. The New Testament: A Historical Introduction to the Early Christian Writings. 5th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012., or Raymond E. Brown. An Introduction to the New Testament. New York: Random House, 1997., or John Dominic Crossan. The Birth of Christianity: Discovering What Happened in the Years Immediately After the Execution of Jesus. Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1998.

See, for example, Helen K. Bond. The First Biography of Jesus: Genre and Meaning in Mark’s Gospel. Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co, 2020.

See, for example, Whitney Shiner. Proclaiming the Gospel: First-Century Performance of Mark. 1st ed. New York: Trinity Press International, 2003.

See, for example, Rudolf Bultmann. Die Geschichte der synoptischen Tradition, 1921. ET: The History of the Synoptic Tradition, rev. edn. with supplement, trans. John Marsh. New York: Harper & Row Publishers, 1963.

Robyn Faith Walsh. The Origins of Early Christian Literature: Contextualizing the New Testament within Greco-Roman Literary Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021. 16.

John Dominic Crossan. Jesus: A Revolutionary Biography. New York: HarperCollins, 1994. 171.

Helen K. Bond. "The Trial and Death of Jesus." In St Andrews Encyclopaedia of Theology, edited by Brendan N. Wolfe et al. University of St Andrews, 2022–. Article published July 18, 2024.

Adele Berlin. Poetics and Interpretation of Biblical Narrative. Sheffield: Almond Press, 1983. 32.

Bond, The First Biography of Jesus, 55.

Love the gospel of Mark and Helen Bonds book over the text. It was influential in my early studies of biblical interpretation. Especially the idea of it possibly being preformed for a public audience at one point. Great work.

I just finished reading Islam Issa's new book about the history of the city of Alexandria, and he has a chapter where he focuses on St. Mark (of Alexandria) and his influence on the early Coptic church. My understanding is that the Christians of that time and place (Clement, Irenaeus, Origen, etc) claim that the same Mark was the author of the Gospel, but that more recent scholarship seems to be skeptical of this. Thoughts?